Giulio Cesare Luigi Canali (1690-1765), parish piest of Sant' Isaia (Bologna), "knew from close range the drama of the 'stomach of the poor': of their flesh, pierced by the chill and hollowed out by ringworm and lice [...]"

"This curate, who lived in such painfully close contact with mendicity, also serves as a precious guide [...], shining the ray of his lantern's light on the most secret aspects of the beggars' lives. He also illuminates the insomnia of the poor, the recurrent and almost obsessive theme of stench, fetor, rags and lurid scarred flesh ('with foul sores, seething throughout the body') [...] and the subject of dirty underpants: [...] who could exaggerate the discomforts of the rubbish, the stench, the emaciation and the squalor whilst these paupers are forced to wear the same underpants for months and months? What Capuchin's most hirsute sackcloth, what penitent's roughest hairshirt, in comparison to these underpants, should not rather be considered the finest linen and delicate sea-silk, particularly given the insufferable troubles that this causes, sordidness which, so to speak, generates rotten flesh. [...] The images which the implacable eye of the Bolognese curate forces us to smell more than observe, are those of the hell of the poor: a putrefied inferno, foul with bodily waste, stagnant faeces and decomposing urine. [...]Whether in the gloomy interiors of their tumble-down hovels ('the shacks, hay-lofts, caves, dungeons, muddy pools, the semi-infernos of the paupers. Oh, spectacles of compassion and horror!' exclaims Canali, 'How many times I nearly fainted for the intolerable stench and fetor! '), or in the total inferno of the prisons, perceived, carnally and viscerally, as the 'universal punishment of all the senses', where the nauseating perception of stench and fetor which impregnates everything dominated obsessively, yet again.

That filth and those faeces, in which it is their need to swim and remain immersed, so that the prison nearly becomes a sewer! What tongue and what ink would suffice to describe the pain that they bear above all, that they would sooner lie on thorns or burning coals than on that rubbish? And yet they are seen reduced to such intolerable extremes of misery, that they could fit almost to the

letter the words of Joel: 'the beasts of burden rotted in their own dung'.

The descent into the depths could not fail to pass through the 'dismal, frightening spectacle' of the hospital: 'theatre of horror', 'residence of tears', 'home of spasms', 'dark region of death: in regione umbrae mortis'. They stagnate in gloomy corridors, where the 'miserable diseased incurables

... the helpless poor', lie amidst the 'stench and horror of their own disgusting sores'.

Stench and fetors assault the sense of smell, screams and laments the hearing, squalid and deformed faces under one's eyes. Some, because of burning fevers, rave and throw whatever is handy; others, also because of fevers, but of opposite type, shiver and clatter their teeth. Some have their heads split by unbearable headaches, others have their ribs broken and guts pierced by acute pleurisy. One who is about to be suffocated by excessive catarrh, and another who thinks a thousand times he is about to die from the incessant attacks of bad asthma, but never dies. There, as a result of a most bitter thirst, one suffering from dropsy struggles impatiently, and here, because of intestinal inflammation, a consumptive is heard to come to his end [...] There are the convulsions and the contractions of the nerves, [...]; there are aqueous hernias, false catarrhs, fistulated sores, tumours of such large size that there is no medicine other than iron and fire (...) so that, doing the necessary both with iron and with fire, in a metamorphosis that is too difficult but otherwise inevitable, the infirmaries become Calvaries, the beds gallows, the doctors ... executioners."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', pp. 68 - 70)

"Strange priests wandered among the pallets of the dying, the attendant fathers of the sick, called fathers 'of Good Death': '[...] Sinister. black as crows, disliked by the sick, they tried to convince them that since diseases were none other than 'a royal road to show us the way to heaven so as to rejoice

in the Divine Essence, they should not decline our attention nor regret it, but should accept and endure with holy will. Better dead but saved than vagabond and sinner, was their logic. In many the 'holy will' was late in showing itself, and this was a shame, because in fact the diseases could

'take away the opportunity of falling into some very grave sin' [Marcello Mansi in the Consigli per aiutare al ben morire (1625)]."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', p. 70)

"The 'poveretti' emerge from the silence of nothingness thanks to the mediation of story-tellers such as Giulio Cesare Croce, Vincenzo Citaredo of Urbino, author, among other works, of the Speranza de' poveri (1588), and Giacomo Cieco Veronese [Lamento nuovo sopra la andata di Tofalo zafo Sbirro de poveri mendichi casa bella e ridicolosa (1593)], and many others, often anonymous.Among the latter there is the author of the Opera nuova. Dove si contiene il lamento della Poverta, sopra la carestia dell'anno 1592, in which the anxiety about bread that 'is in size / like a bird's egg', the feeling of being 'poor creatures' in the hands of monopolizers and usurers, powerless and wretched [...], is moderated by the acceptance of the unavoidable fatality of famine sent to those with 'evil phalluses', and in homage to the established powers. [...] The entire poem is punctuated by this obsessive call to patience and forbearance, the exhortation to be suspicious of false prophets and professional troublemakers, the shuddering call to the great journey to Kingdom of Shadows, the appearance of old late-medieval motifs and the re-emergence of death's lugubrious triumphs."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', p. 71)

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', p. 71)

"The opinion that famine and plague were signs of divine wrath, caused by the corrupt and wicked habits of men was widespread. Many held that famine was brought about by natural causes like the 'irregularity of the weather and the altered seasons' , but most, uninfluenced even by the political side of the unequal distribution of resources, believed that it was divine anger which punished excesses, 'debauchery, discord and lust'.A good portion of the population swore that it was not the 'corruption' of the air, 'the putrefied inferior elements', the eating of 'rotten fish', the action of 'wicked ministers' in the service of the Turk, or the coming and going of 'merchandise', but the angel of the angered God which generated the scourge.

The Bolognese druggist Pastarino was firmly convinced of of this. In his Preparamento ... per medicarsi in questi sospettosi tempi di peste [1577], while he noted the frequent outbreak of the plague in the 'two most mercantile cities of Italy', he swore that the 'many iniquities ... that are performed in transactions, dealings and trading moves God to send some of his terrible scourges and, in particular, pestilence'.

Both herb vendor and preacher, he exhorted his fellow-citizens to dry out 'this our body full of grease and humidity'. This is in accordance with Galen's precept, 'It is proper to dry up the body in this way, and keep it dry', and reinforced by the authority of Avicenna, according to whom 'The best treatment of them [those ill with... pestilential fevers] is desiccation, and it is best that their foods be dried.' Preacher of sobriety and abstinence ('one lives better with little), this singular and ambiguous spice merchant - citing Galen ('it is proper to open up the blocked pores') - called for the opening up of the soul before the body.

'And what are these blocked pores if not our own ears, deaf to sermons, and our mouths, closed to confessions? These should be opened, because by doing so the infirmities are discovered, the bad

humours are revealed, we recognize our worst qualities and, better, they are more easily restored to health ... Having done this, it is necessary to conclude with a good evacuation and make every effort

to evacuate all the superfluities that are within us. Thus we have the rule given to us by Galen that 'convenit corpus superfluitatibus plenum evacuare'. And Avicenna as well ... used these words: 'Purging and loosening is very useful as is the evacuation of the stomach in treating the plague'.

Let us now accept as a principle, my fellow-citizens, to evacuate from this our body every superfluity that is found here. Superfluous are the evil thoughts, dishonest reasoning and wicked designs that

occupy the mind. Superfluous are the lascivious glances, malicious signs and curiosities that dominate the eyes. Superfluous are vain things ... superfluous swearing . . . Superfluous are the things of others that we wrongly keep. And superfluous is still all that with which we could help the poor but do not ... Let us therefore protect ourselves from divine anger, and with this complete evacuation of the body . . . let us prepare to treat ourselves. '

It is not easy to say how much the voice of this Bolognese druggist was heard, seemingly bizarre in the play of extravagant comparisons between apothecary culture and pastoral ideology."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', pp. 72-73)

The Bolognese druggist Pastarino was firmly convinced of of this. In his Preparamento ... per medicarsi in questi sospettosi tempi di peste [1577], while he noted the frequent outbreak of the plague in the 'two most mercantile cities of Italy', he swore that the 'many iniquities ... that are performed in transactions, dealings and trading moves God to send some of his terrible scourges and, in particular, pestilence'.

Both herb vendor and preacher, he exhorted his fellow-citizens to dry out 'this our body full of grease and humidity'. This is in accordance with Galen's precept, 'It is proper to dry up the body in this way, and keep it dry', and reinforced by the authority of Avicenna, according to whom 'The best treatment of them [those ill with... pestilential fevers] is desiccation, and it is best that their foods be dried.' Preacher of sobriety and abstinence ('one lives better with little), this singular and ambiguous spice merchant - citing Galen ('it is proper to open up the blocked pores') - called for the opening up of the soul before the body.

'And what are these blocked pores if not our own ears, deaf to sermons, and our mouths, closed to confessions? These should be opened, because by doing so the infirmities are discovered, the bad

humours are revealed, we recognize our worst qualities and, better, they are more easily restored to health ... Having done this, it is necessary to conclude with a good evacuation and make every effort

to evacuate all the superfluities that are within us. Thus we have the rule given to us by Galen that 'convenit corpus superfluitatibus plenum evacuare'. And Avicenna as well ... used these words: 'Purging and loosening is very useful as is the evacuation of the stomach in treating the plague'.

Let us now accept as a principle, my fellow-citizens, to evacuate from this our body every superfluity that is found here. Superfluous are the evil thoughts, dishonest reasoning and wicked designs that

occupy the mind. Superfluous are the lascivious glances, malicious signs and curiosities that dominate the eyes. Superfluous are vain things ... superfluous swearing . . . Superfluous are the things of others that we wrongly keep. And superfluous is still all that with which we could help the poor but do not ... Let us therefore protect ourselves from divine anger, and with this complete evacuation of the body . . . let us prepare to treat ourselves. '

It is not easy to say how much the voice of this Bolognese druggist was heard, seemingly bizarre in the play of extravagant comparisons between apothecary culture and pastoral ideology."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', pp. 72-73)

"The elettuario de sanguinibus ('blood electuary') was a speciality of Pastarino's shop, to which the Senate of Bologna had conceded the privilege of publicly preparing, on the second day of August, the antidotes with which the city,[...] prepared for the 'defence' of its citizens as if for soldiers 'enclosed in a strong and well-fortified castle', in order to resist the attack of diseases.

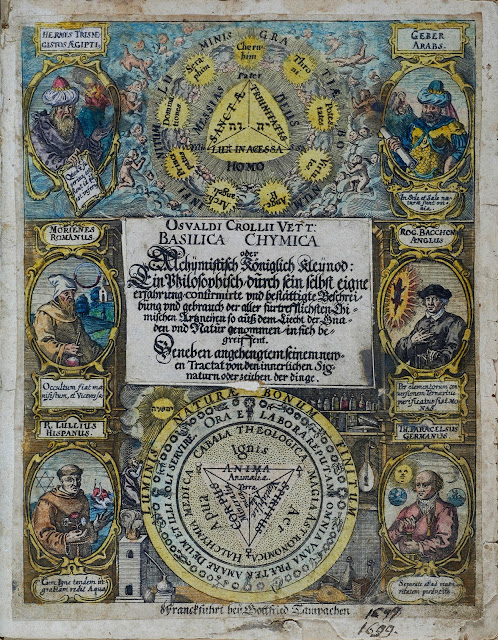

The turnover of cash around the druggists' shops was considerable. It is known that two pharmacopoeias existed, one for the rich - full of expensive rarities like 'ambergris', 'bezoar-stone', 'unicorn stone', rubies and gold - and one for the poor, much more modest, almost entirely vegetable. The Fabrica de gli spetiali by Prospero Borgarucci (1566), Valerio Cordo's Dispensarium (1554), Johann Schroeder [1600-1664]'s Thesaurus pharmacologicus, Osvaldus Crollius [1563 - 1609]' Basilica chymica and Ludovico Locatelli's Theatro d'arcani [1644], presupposed buyers with unlimited available finances."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', p. 73)

|

| Osvaldus Crollius, Basilica Chymica, Chemical Heritage Foundation, Public Domain |

Ludovico Locatelli, Theatro d'Arcani, 1644 edition

|

The turnover of cash around the druggists' shops was considerable. It is known that two pharmacopoeias existed, one for the rich - full of expensive rarities like 'ambergris', 'bezoar-stone', 'unicorn stone', rubies and gold - and one for the poor, much more modest, almost entirely vegetable. The Fabrica de gli spetiali by Prospero Borgarucci (1566), Valerio Cordo's Dispensarium (1554), Johann Schroeder [1600-1664]'s Thesaurus pharmacologicus, Osvaldus Crollius [1563 - 1609]' Basilica chymica and Ludovico Locatelli's Theatro d'arcani [1644], presupposed buyers with unlimited available finances."

(Camporesi 1996, '5. 'They Rotted in Their Own Dung'', p. 73)

|

| Ambergris |

[Ambergris: "a solid, waxy, flammable substance of a dull grey or blackish colour produced in the digestive system of sperm whales. [...] Ambergris has been mostly known for its use in creating perfume and fragrance much like musk. Perfumes can still be found with ambergris around the world. It is collected from remains found at sea and on beaches [...] During the Black Death in Europe, people believed that carrying a ball of ambergris could help prevent them from getting the plague. This was because the fragrance covered the smell of the air which was believed to be a cause of plague. This substance has also been used historically as a flavoring for food and is considered an aphrodisiac in some cultures. During the Middle Ages, Europeans used ambergris as a medication for headaches, colds, epilepsy, and other ailments." (Wikipedia, dd. 26/02/2016)]

|

| Elephant bezoar |

|

| Unknown, Goat bezoar, 16th century, Wien, Kunsthistoriches Museum (Kunstkammer) |

[Bezoar: " a mass found trapped in the gastrointestinal system (usually in the stomach); Bezoars were sought because they were believed to have the power of a universal antidote against any poison. [...] In 1575, the surgeon Ambroise Paré described an experiment to test the properties of the bezoar stone. At the time, the bezoar stone was deemed to be able to cure the effects of any poison, but Paré believed this was impossible. It happened that a cook at King's court was caught stealing fine silver cutlery and was sentenced to death by hanging. The cook agreed to be poisoned instead. Ambroise Paré then used the bezoar stone to no great avail, as the cook died in agony seven hours later. Paré had proved that the bezoar stone could not cure all poisons as was commonly believed at the time.

Modern examinations of the properties of bezoars by Gustaf Arrhenius and Andrew A. Benson of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography have shown that they could, when immersed in an arsenic-laced solution, remove the poison. The toxic compounds in arsenic are arsenate and arsenite. Each is acted upon differently, but effectively, by bezoar stones. Arsenate is removed by being exchanged for phosphate in the mineral brushite, a crystalline structure found in the stones. Arsenite is found to bond to sulfur compounds in the protein of degraded hair, which is a key component in bezoars." (Wikipedia, dd. 26/02/2016)]

|

| Unicorn Horn / Narwhal tooth |